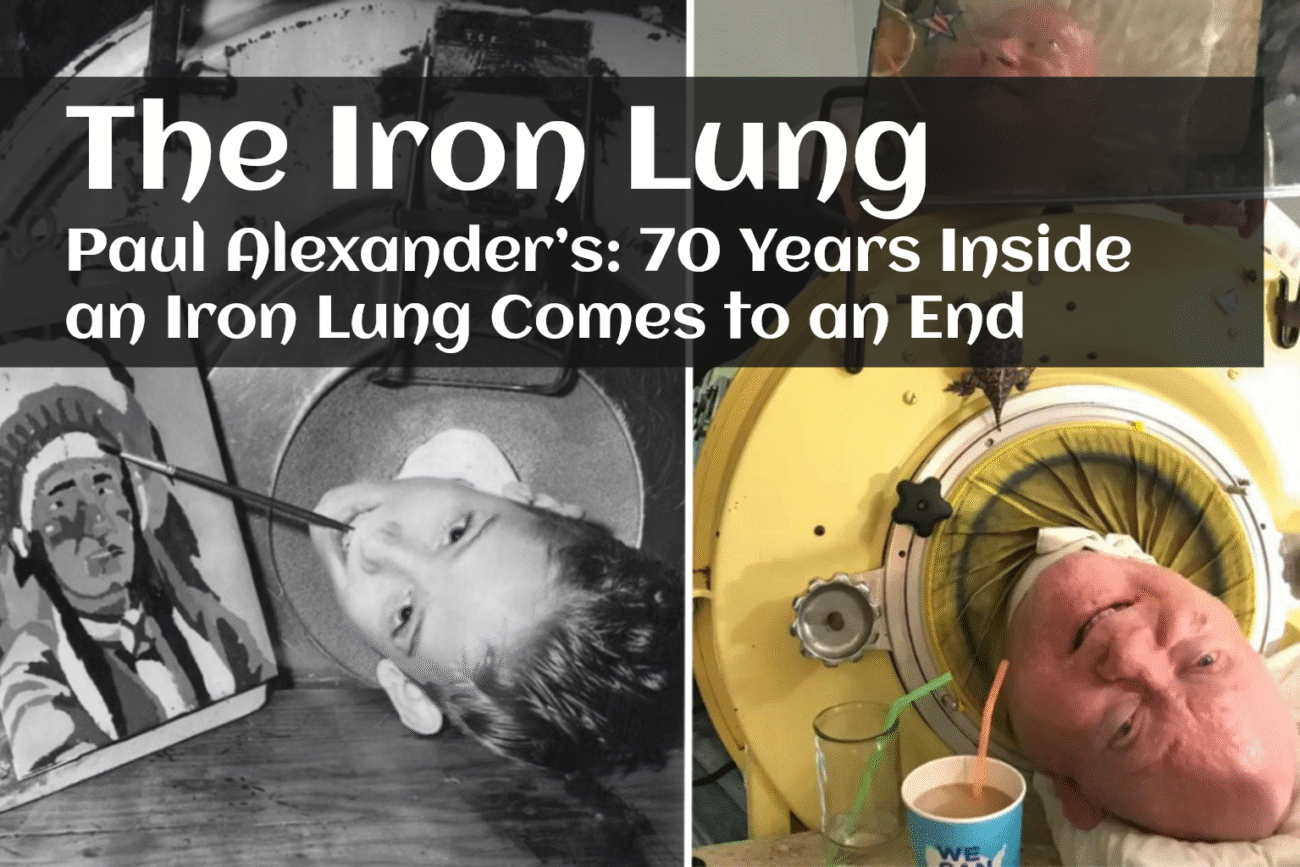

For seventy straight years Paul Alexander lived almost every hour inside a huge metal breathing machine. Doctors called the device an iron lung. Reporters called Alexander the longest-living polio survivor on record. Friends called him unstoppable. From 1952 until his peaceful passing in March 2024, he proved that a child struck down by polio could still grow up, earn a law degree, champion disability rights, and inspire the world to trust the polio vaccine that might have saved him. His journey is at once heartbreaking and deeply hopeful.

A Sudden Fever in the Summer of 1952

Dallas, Texas, was baking in August heat when six-year-old Paul Alexander felt a sharp ache in his neck. Within twenty-four hours he could not lift his legs. Parkland Hospital hallways were jammed with stretchers. Polio season had arrived, and the enemy virus was everywhere. Doctors diagnosed paralytic polio and warned the family Paul might not survive the night unless a vacant iron lung could be found.

Meeting the Iron Lung

Late that evening an orderly wheeled in a yellow cylinder weighing more than eight hundred pounds. Nurses slid Paul onto a narrow tray, sealed his neck with rubber gaskets, and switched on the motor. Negative pressure pulled his chest upward, then released it. Mirrors above his face let him see the ward, but every reflected child was fighting the same war against breathlessness.

Days of Fear, Moments of Grace

Polio kills by paralyzing the muscles that move air. In 1952 more than 57,000 Americans caught the virus; thousands needed iron lungs. Amid the chaos, little acts of kindness mattered. A volunteer hung bright paper stars on Paul’s chamber so he would know day from night. A nurse read comic strips aloud. Each small grace reminded the polio survivor that people still saw the boy, not just the machine.

Homecoming in a Truck

Eighteen months later Paul Alexander was alive yet still completely paralyzed below the neck. Parkland released him on one condition: the family had to supply constant electricity. Paul’s father rented a flat-bed truck and a gasoline generator. Neighbors watched in silence as the yellow iron lung rumbled into the living room. From that day forward the household revolved around twelve-second breathing cycles, oiling pistons, and praying the power would not fail during Texas storms.

Learning to “Frog Breathe”

A physical therapist named Mrs. Sullivan taught Paul glossopharyngeal breathing frog breathing. He had to gulp air, trap it, then force it into his lungs. She promised him a puppy if he could stay outside the chamber for three minutes. Months later the room erupted in cheers: Paul reached the mark and earned Ginger. That trick later let him exit the steel respirator for short periods, attend classes, and even travel.

School Without Hallways

Public schools had no blueprint for a boy who slept in metal. Teachers visited the house, slid flashcards under mirrors, and discovered Paul Alexander had a phenomenal memory. By high-school age he persuaded administrators to let him graduate with his class. On commencement day 1967 custodians rolled the gleaming iron lung into the auditorium so Paul could receive his diploma to thunderous applause. The newspaper headline read “Teen in Lung Ranks Second in Class!”

College Dreams and Legal Ambitions

Scholarship in hand, the young polio survivor pushed further. Southern Methodist University first rejected him. He appealed, won admission, then transferred to the University of Texas at Austin. Each lecture meant parking a van near the classroom, performing frog breathing, and speaking answers while classmates scribbled notes. After earning a history degree he entered law school. Picture the scene: a heated moot-court final, one student upright in a modified wheelchair, calm and razor-sharp.

Enjoy playing the Wordle game, where you can challenge your mind and language skills by trying to guess the hidden word within a limited number of attempts. Each guess provides you with clues about the correctness and position of the letters, adding excitement and suspense to every round.

Sworn In with a Thumb

In 1986 Paul Alexander passed the Texas bar exam. He could move only his head, yet insisted on taking the oath in person. The judge asked him to raise a hand; instead Paul lifted a single thumb a few millimeters a feat of pure will. Courthouse ramps were scarce, so friends muscled his chair over steps. Those struggles seeded his fight for disability rights. Long before the ADA, Paul wrote letters, gave interviews, and reminded officials that access is a civil right, not a favor.

Practicing Law from a Lung

Clients visited his Dallas apartment, marveling at the humming capsule in the corner. Paul drafted legal briefs with a plastic stick held between his teeth, tapping each key on an IBM Selectric. In court he spoke with eloquence, pausing every few minutes to sip air through practiced frog breaths. His specialty was family law cases that needed empathy as much as statutes. More than once he joked, “I bill by the hour, not by the breath.”

A Symbol in the Age of Vaccines

While Paul built a career, the polio vaccine transformed public health. Jonas Salk’s shot in 1955 and Albert Sabin’s oral drops in 1961 slashed American cases to near zero by the late seventies. Iron-lung wards emptied, their machines rolled into storage. Yet one cylinder stayed busy in Dallas. Reporters revisited Paul Alexander again and again, calling him proof that immunization matters. He responded graciously, repeating a simple plea: “Please vaccinate your kids.”

A Social-Media Star at Seventy-Five

In 2020 a TikTok clip of the aging polio survivor inside his vintage iron lung went viral. Teen viewers asked millions of questions. Paul answered through a plastic tube, voice steady: “I’m still breathing, still reading, still grateful.” Within months he had half a million followers and a fresh platform for urging vaccination and disability rights.

Keeping the Machine Alive

Replacement parts vanished decades ago, so Paul relied on ingenuity. A scuba-gear shop crafted new rubber cuffs. A retired engineer 3-D-printed bellows hinges. When the main motor failed in 2015, an online fan located a spare machine in a barn; volunteers restored it in one weekend. Each rescue showed how fragile his safety net remained.

What It Feels Like Inside a Lung

Paul often described the sensation. Lying flat, he felt the vacuum pull his ribs upward, then shove them down. The rhythm was relentless around five breaths a minute, half a million a week. During storms he listened for pitch changes that signaled motor strain. Yet the iron lung also offered comfort: warm air, familiar mirrors, and a percussive lullaby that lulled him to sleep. He called it “old faithful,” half-joking, fully thankful.

The Wider Story of Polio

Before the polio vaccine, polio terrorized nations. In 1916 New York saw 27,000 cases. By 1952 the U.S. peak hit 57,000. Summer closures of pools and theaters became routine. Thanks to vaccination, wild poliovirus now survives only in two countries. Disability rights advocates warn that vaccine hesitancy could allow a comeback. Paul’s life turns statistics into flesh: one child, one virus, seventy years in metal custody.

The Iron Lung: How It Works and Why It Became Obsolete

The iron lung is a large, metal machine that helps people breathe when their muscles can’t do it themselves. It looks like a big cylinder, and the patient lies inside it with only their head outside. The machine works by creating a gentle vacuum inside the cylinder that pulls the chest open, allowing air to flow into the lungs. Then the pressure returns to normal, and the chest muscles relax, pushing air out. This process mimics natural breathing and keeps the patient alive when their own lungs cannot work properly.

In the mid-1900s, the iron lung was a lifesaver for thousands of polio survivors whose breathing muscles were paralyzed. However, with the invention and widespread use of the polio vaccine, fewer people got the disease and needed this machine. At the same time, new breathing machines called positive-pressure ventilators were developed. These modern machines push air directly into the lungs through tubes and are smaller and easier to use. Because of this, the iron lung slowly disappeared from hospitals and homes. Today, only a few people still use it, making it a symbol of medical history and the fight against polio.

Fighting for Accessibility

The 1990 ADA outlawed public-place discrimination, but success required role models. Paul Alexander appeared at rallies, testified before councils, and wrote op-eds explaining how curb cuts and lever handles help everyone. He urged architects to imagine rolling a hospital bed through every doorway they designed.

Writing Three Minutes for a Dog

At sixty-eight Paul began typing a memoir. He balanced a pointer between his teeth, tapped fifty times to form each short word, and rested often. The task consumed eight years. In 2020 he self-published Three Minutes for a Dog. Readers devoured the honest prose: childhood nightmares, teenage crushes glimpsed in the mirror, courtroom victories, and the day his mother passed away while he lay powerless to hug her.

Final Years and Farewell

Late in 2023 Paul Alexander caught a respiratory infection and spent Christmas in hospital. He rallied, but on 11 March 2024 he quietly slipped away at seventy-eight. News outlets worldwide ran tributes. One follower wrote, “His life proves courage is contagious.”

The Impact He Leaves Behind

Today only a single American still relies full-time on an iron lung. Yet the yellow cylinder in Dallas has not disappeared; it sits in a museum, humming gently under low light. Schoolchildren press faces to glass, hearing the pump that breathed for a boy who refused to be limited. Guides repeat his mantra: take the polio vaccine, support disability rights, and never underestimate a determined spirit.

A Ripple Spreading Outward

Months after his passing, teachers assign essays on Paul’s resilience, engineers study negative-pressure ventilation, and health officers quote his interviews to counter vaccine myths. Each ripple shows how one story can spark systemic change and how a man once told he would die young changed countless lives instead.

Conclusion

Seventy years. One machine. Endless influence. Paul Alexander turned a mechanical prison into a platform, transformed tragedy into a legal career, and reframed the narrative of what a polio survivor can achieve. He reminded us that the polio vaccine is a miracle we must never take for granted and that disability rights are human rights worth defending. Above all, he showed that breath, hope, and courage often arrive in twelve-second intervals, whispered by an old iron lung that never gave up on its passenger.

Discover the world’s most iconic public squares, where history, culture, and vibrant life come together. Explore breathtaking architecture and lively atmospheres in our top 12 picks. Dive into the heart of global cities visit now and experience these unforgettable urban gems!