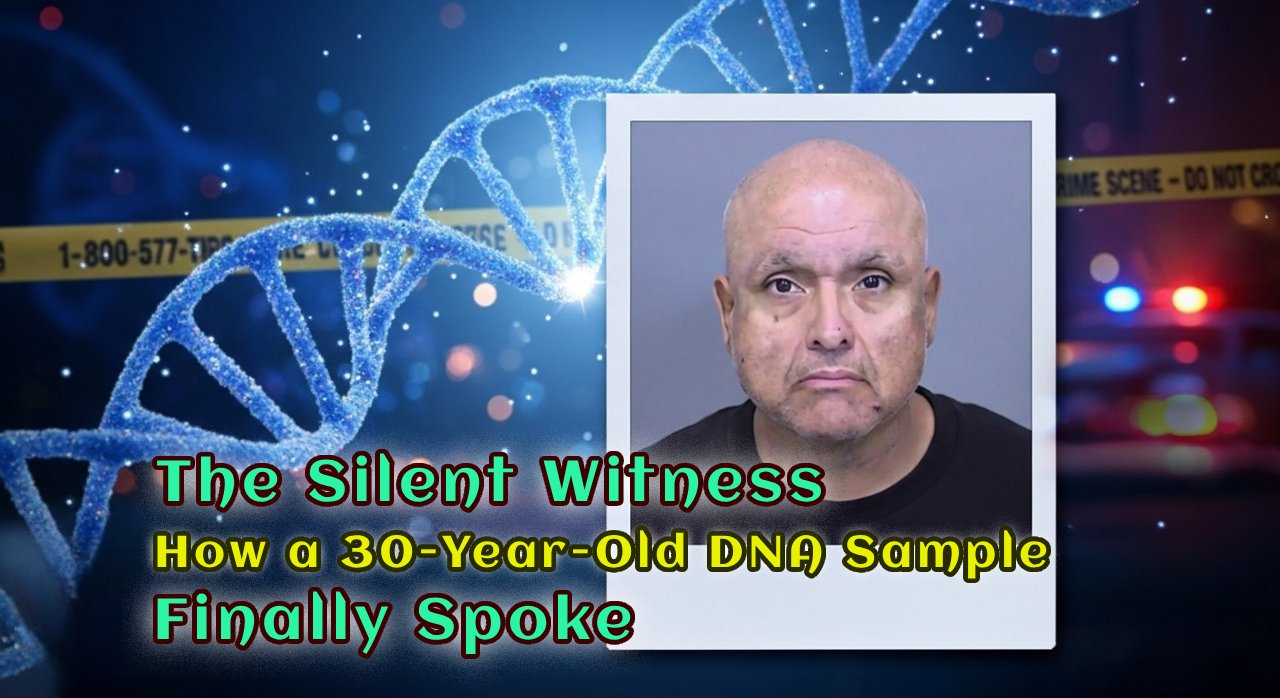

For three decades, it was a ghost in the machine. A digital file, a genetic profile without a name, born from a brutal 1994 assault in Ventura County, California. The case had long gone cold, a testament to the frustrating limits of police work at the time. The victim, who had courageously fought her way to freedom, was left in a state of suspended justice. Then, in 2024, the silence broke. A new initiative breathed life into the dormant evidence, and that old sample was re-tested. The result was a sudden, jarring alert from the nation’s DNA database. The ghost finally had a name: Abraham Ramirez. nbcnews

This single breakthrough is more than just one closed case; it’s a window into a quiet revolution in criminal justice. It demonstrates the incredible power of solving cold cases with DNA, where science reaches back through time to unmask predators who thought they had gotten away with it. This is the story of how a single piece of evidence, patiently waiting in a locker, can unravel a web of violence spanning multiple states and decades, rewriting the rules for crimes once considered unsolvable.

A Predator’s Shadow: The Unsolved Crimes of the 90s

The path to identifying Abraham Ramirez started with a terrifying crime and a victim’s remarkable will to live. It’s a stark reminder of why preserving evidence, even when hope seems lost, is the most crucial step in any investigation.

In 1994, a woman in Ventura County was abducted and assaulted. In an act of incredible bravery, she escaped. In the aftermath, a sexual assault kit collected the biological traces her attacker left behind. At the time, with no suspect, this kit was a message in a bottle, holding a genetic secret that wouldn’t be read for 30 years. That single act of collecting DNA evidence laid the foundation for a case that would one day stun investigators.

Despite this vital evidence, the investigation stalled. With no witnesses or leads, the case file grew thick with reports but thin with hope. The sexual assault kit joined a vast national backlog of unprocessed evidence. The case went “cold” a term law enforcement uses when all investigative avenues have been exhausted.

For years, the assault was seen as an isolated tragedy. The truth was far more sinister. When the DNA from that 1994 kit was finally analyzed with modern tools, it didn’t just identify a suspect; it linked him to a string of other cold cases. The genetic fingerprint was a perfect match to DNA evidence from four unsolved assaults in Phoenix, Arizona, spanning from 1998 to 2013.

This revelation transformed the narrative. It wasn’t one crime; it was the work of a serial predator operating for nearly two decades. The failure to solve the first case had allowed a dangerous man to continue his attacks. An unsolved violent crime is not a static event filed away in a cabinet; it is an ongoing threat. The successful effort in solving cold cases with DNA didn’t just bring justice to one victim, but potentially saved future ones.

The Science of Second Chances: Reawakening Old Files

The Ramirez case illustrates a fundamental shift in modern policing. Files once relegated to dusty shelves are now viewed as solvable puzzles, waiting for the right key. This change is driven by dedicated initiatives and, above all, revolutionary advances in forensic science.

A case goes cold for many reasons no witnesses, no suspects, or forensic tools that weren’t up to the task. But a case being cold doesn’t mean it’s a dead end. The decision to reopen an investigation is almost always sparked by new capabilities, primarily in forensic science. Evidence once considered too small, old, or degraded can now yield a full DNA profile.

The breakthrough in the Ramirez case was a direct result of the Ventura County Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (VCSAKI), a program designed to revisit old evidence with new technology. This proactive approach is changing law enforcement. Instead of passively waiting for a lucky break, cold case units are now actively hunting for answers in their own evidence lockers. The success of forensic science has proven that for many old crimes, the evidence was there all along; we just needed the right tools to read it.

The process of turning a 30-year-old sample into a definitive profile is a marvel of modern science. After extracting the DNA from the cells, scientists use a technique called Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). This acts like a biological copy machine, making millions of copies of the specific DNA segments needed for analysis. It’s this amplification that makes solving cold cases with DNA possible, allowing a full profile to be generated from a sample that was previously useless. The evidence didn’t change over 30 years, but our ability to decipher its secrets did.

The Digital Detective: A Match in the CODIS Database

Once scientists generated a clear DNA profile, they needed to connect it to a person. That connection was made through a powerful federal tool: the Combined DNA Index System, or the CODIS database. This national system acts as a silent, constantly working detective.

Established in the 1990s, the CODIS database is the FBI’s nationwide network of DNA profiles from labs across the country. It allows investigators to compare DNA evidence from crime scenes against millions of known profiles. The system works by comparing profiles stored in two key indexes:

- The Offender Index: Contains DNA profiles from individuals convicted of serious crimes.

- The Forensic Index: Contains “ghost” profiles developed from unknown sources at crime scenes.

When a new profile is uploaded, the software automatically searches for a match. An “Offender Hit” occurs when a crime scene profile matches a known individual. This is the moment a ghost gets a name.

The resolution of the Ventura County case was a textbook example. When the newly generated DNA profile was uploaded to the system, the CODIS database performed its relentless search. It found a match. The unknown profile from 1994 was identical to that of Abraham Ramirez, whose DNA was already in the Offender Index. After three decades of silence, the search was over.

Beyond the Database: The Power of Genetic Genealogy

But what happens when a killer’s DNA isn’t in a criminal database? A revolutionary technique has emerged to solve even those cases: investigative genetic genealogy. This method doesn’t look for the suspect directly; it looks for their family.

Investigative genetic genealogy combines advanced DNA analysis with traditional family tree research. It gained international fame with the identification of the “Golden State Killer” and is now a game-changer for the most difficult cold cases. While CODIS seeks an exact match, genetic genealogy searches public ancestry websites for people who share enough DNA with the suspect to be a relative even a distant cousin.

The process is a blend of science and detective work. Scientists generate a detailed profile and upload it to public genealogy databases like GEDmatch. When the database identifies genetic relatives, investigators build out their family trees using public records, working backward to find a common ancestor and then forward to identify potential suspects. The lead is then confirmed with a direct DNA sample.

The capture of Joseph James DeAngelo is the ultimate proof of its power. For decades, his DNA linked numerous crimes in the Forensic Index of the CODIS database, but since he’d never been convicted of a qualifying felony, there was no match. The case was frozen until 2018, when investigators used genetic genealogy. They found his distant relatives, built a family tree that pointed to him, and confirmed the lead. One of America’s most terrifying crime sprees was finally over.

Justice for the Long-Forgotten

The Ramirez and Golden State Killer cases are not isolated miracles. They are part of a growing wave of resolutions that bring answers to families who have waited a lifetime. One of the most compelling examples is the 1972 murder of Jodi Loomis. She was killed years before DNA was even a concept in forensics. Yet, investigators had the foresight to preserve biological evidence from her boots.

For 47 years, that evidence sat in storage. In 2019, it was submitted for genetic genealogy analysis. The technique pointed to Terrence Miller, a 78-year-old man who was confirmed as the killer. The resolution of a crime from 1972 demonstrates a profound principle: the meticulous police work of the past has been retroactively empowered by the technology of the future.

These stories send a powerful message: for perpetrators of violent crimes, the passage of time is no longer a shield. The evidence left behind at a crime scene is patient, and the technology used to analyze it is becoming more relentless every year. This new era of solving cold cases with DNA offers a profound sense of hope that even in the darkest and most forgotten cases, the truth can still be found. However, this power also opens a vital debate about genetic privacy, forcing society to grapple with how to balance the immense benefit of this tool with the fundamental right to privacy.

The story of Abraham Ramirez, hidden for 30 years, stands as a testament to the fusion of dogged police work and brilliant science. It shows that the truth may be locked away in the nucleus of a single cell, patiently waiting for the right key to finally bring it into the light.

Nicole Michelle Johnson, a Baltimore mother, hid her two children’s bodies in her car’s trunk. The horrific truth was discovered after a car crash, shocking the nation. Read The Full Story